We will all remember what we doing when hearing the news that the great Arnold Palmer passed away.

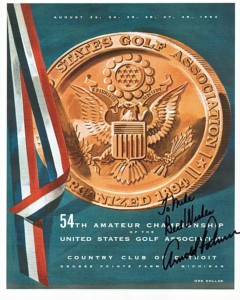

Since capturing the golf world’s heart in 1954 when he won the U.S. Amateur Championship tournament at Country Club of Detroit, Mr. Palmer has been a giant. His spirit and good will around the golf world will be sorely missed.

There are so many special moments on and off the course that will be remembered. Below is an excerpt from The United States Amateur: The History and Personal Recollections of Its Champions that discuss the day “amateur golf lost its crown prince and professional golf gained its future king.”

For nearly all of his adult life, Arnold Palmer has been one of golf’s most beloved figures. The son of a teaching professional from Latrobe, PA, he made charisma a household word in the early 1960’s. Winner of four Masters, tow British Opens and a U.S. Open during a thrilling seven-year span from 1958 to 1964, Palmer remained the undisputed king of golf long after his competitive prime. As last as his Masters farewell in 2004-culminating in a prolonged standing ovation as he walked up the eighteenth fairway for the last time-the love affair between Palmer and the golfing populace has been undying.

However, before there was Arnold Palmer the professional, the go-for-broke aggressor who perfected the final-round charge in front of adoring galleries swarming him tee to green, there was just Arnold D. Palmer, a Cleveland-area amateur golfer and industrial-paint salesman with tremendous potential. It is difficult to appreciate in hindsight, but in the summer of 1954, when he would win the Amateur at the Country Club of Detroit, Palmer’s future in professional golf wasn’t inevitable. He had not demonstrated that his game could compete with the leading professional players of that era, players like Ben Hogan, Sam Snead, Cary Middlecoff and Lloyd Mangrum. Although he had achieved success as a college golfer, at Wake Forest University, and had won the Western Pennsylvania Amateur five times between 1948 and 1952, he was still considered a rung below the finest amateurs in the country.

In the fall of 1950, Palmer dropped out of college and enlisted in the Coast Guard for three years following the tragic death of his teammate and close friend Bud Worsham. After nine months in Cape May, NJ, he was reassigned at the end of 1951 to Cleveland and placed under the command of Admiral Rainey, a golf enthusiast who permitted him to play and practice as much as he liked the following spring. He emerged from a hiatus in the summer of 1953 to win the Ohio amateur and Cleveland Amateur. That same summer Palmer entered his first U.S. Open, played at Oakmont, and missed the cut. In September 1953 he returned to the Amateur at the Oklahoma City Golf & Country Club after a two-year absence. After defeating defending champion Jack Westland in the second round and Ken Venturi in the third, he lost to an Ohioan named Don Albert. That summer renewed Palmer’s enthusiasm for the game: I was disappointed but not discouraged,” he wrote in A Golfer’s Life, his autobiography with James Dodson, published in 1999”. The confidence I felt in my game was almost frightening, and the rekindled desire to play was practically all-consuming. When winter came and the private clubs around Cleveland closed down, several of us routinely went down to Lake Shore golf course and beat balls at frozen cups. Golf nuts in woolies”.

When his Coast Guard service was completed, in January 1954, Palmer returned to Wake forest, where his scholarship had been reactivated, and he played exceptionally well that spring, winning the ACC championship as well as small invitationals and pro-ams. Palmer let his heavy golf schedule interfere with his academic responsibilities, preferring instead to play 36 holes a day. At the end of that semester, a few credits shy of completing his degree in business, he accepted an offer from Bill Wehnes to become a sales rep in his Cleveland-area company, specializing in industrial paints and tapping compound, a substance used to cool metal when holes were drilled through it. Wehnes was well aware of his employee’s ambition to play golf at a higher level, so he let Palmer spend his weekday mornings making sales calls and his weekday afternoons, and weekends golfing at Wehnes’s club, Canterbury.

If there was any foreshadowing of Palmer’s Amateur win, it occurred in early August, two weeks before, at George S. May’s All-American tournament at Tam O’Shanter Country Club, outside Chicago. Palmer finished low amateur nine strokes ahead of the next amateur, Frank Stranahan, tow-time winner of the British Amateur and possibly the finest amateur player of the day. The next week, in May’s World Championship of Golf, Palmer again played well, finishing one shot behind Stranahan for low-amateur honors.

The following week Palmer arrived at the Country Club of Detroit, in the elegant suburb of Grosse Point Farms, one of 200 hopefuls. He survived several close matches, including one over Frank Stranahan in the fifth round and a 39-hole nail-biter over Ed Meister in the semi-finals. Then in the finals Palmer quickly fell behind Robert Sweeny and was two down after the morning round. He still trailed by one after the twenty-ninth hole, which set the stage for the kind of dramatic comeback that would become his trademark: mostly brilliant, occasionally erratic, but always aggressive.

Palmer did not want to turn pro right away. He was looking forward to the Walker Cup at St. Andrews in the spring of 1955, and he wanted to accomplish what Ward and Stranahan had done- win the British Amateur. But a week after prevailing in Detroit, Palmer was invited to and event at Shawnee-on-the-Delaware that began over Labor Day weekend, a tournament he could not have attended without the approval of Bill Wehnes. On the Monday of his arrival, Palmer was introduced to Winifred Walzer, one of the tournament’s official hostesses, and he instantly became smitten. The next day Winnie briefly followed him on the course, and over the next three days they plunged into a courtship. During dinner that Friday night he proposed to her. He planned to take Winnie to Great Britain for their honeymoon the following spring during his Walker Cup visit, but Palmer realized during the ensuing weeks the grim reality of a lifestyle supported by his salary as a paint salesman. He could not even afford to buy Winnie and engagement ring without the unsolicited help of friends in Cleveland. He felt he had no alternative but to take his chance on the pro tour. On November 18, Palmer, with “mixed emotions,” notified the USGA of his decision to forgo his amateur status: “Yet, I can’t overlook my life ambition to follow in the footsteps of my father. We both have counted on this since I started playing golf fourteen years ago. My good fortune in competition this year indicated it is time to turn to my chosen profession”.

Just like that, amateur golf lost its crown prince and professional golf gained its future king.

To read more from our U.S. Amateurs Champions page click here.